Terra (Earth)

In the temple of the Good Goddess on the Aventine Hill in Rome,

non-poisonous snakes roamed freely in the precincts to encourage the fertility

of female clients.

At least as far back as Minoan times, snakes were associated with the life-giving

powers of an Earth-goddess

(Gaia, Cybele, Terra, etc.).

In the later Roman Mithraic cults, the serpent symbolised the passage of the sun along the ecliptic.

The benign attributes of snakes survived their Judæo-Christian demonisation for a remarkably long time.

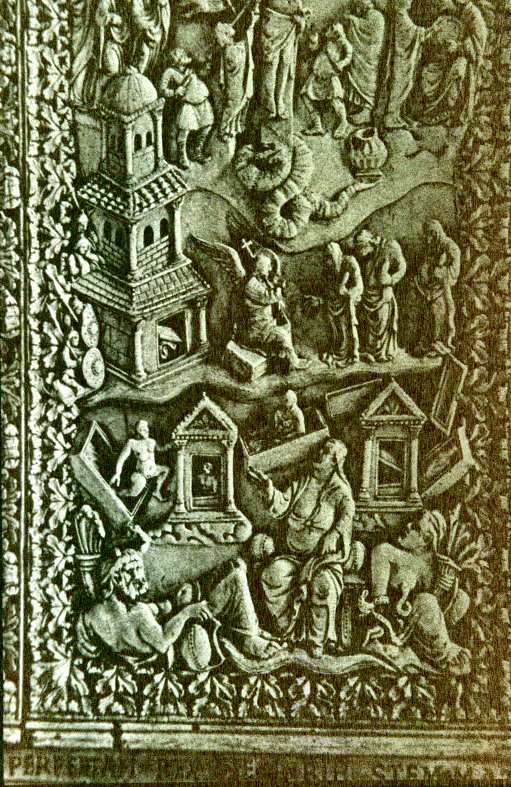

Thus a 9th century ivory book-cover possibly from Rheims depicts the Resurrection

of the Dead

leaving rather Roman mausolea to join the saints in the New Jerusalem,

viewed with satisfaction by Oceanus (bottom left), Roma (a matron!) and Terra

suckling a curling snake.

Interestingly, the snake-as-Satan also features at the base of the Crucifixion.

now in the Stadtsbibliothek in Munich

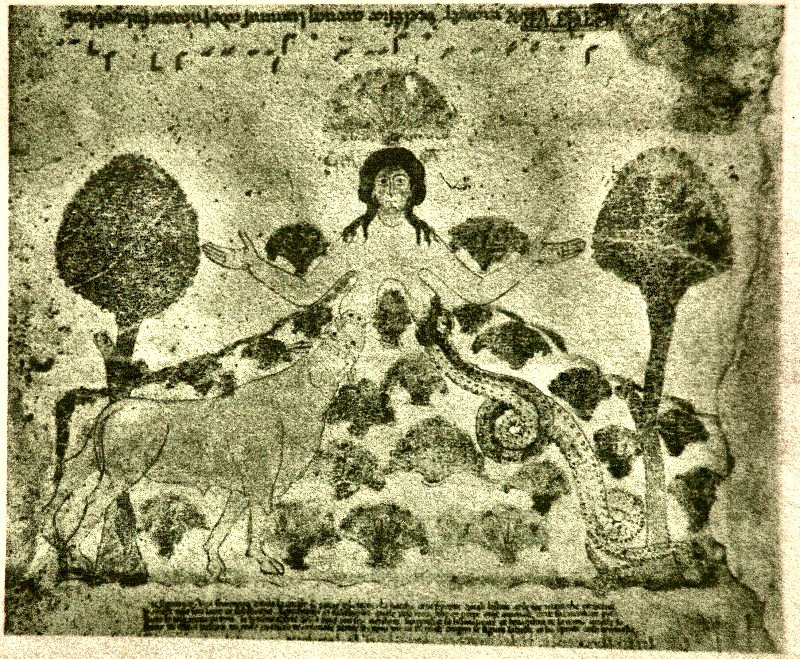

Even later, in the 11th and 12th centuries, on the psalm-sheets known as Exultet

Rolls because their first word was Exultet (Rejoice!)

Terra (always decently clothed) appears nurturing various animals, including

bullocks, does, stags and snakes.

from Monte Cassino, now in the Apostolic Library, the

Vatican

This remarkable capital in the remarkable cloister of Santa Sofia at Benevento

in Calabria (Italy)

shows a naked Terra (with overtones of Luxuria, and without Cornucopia) suckling

an ox and a snake...

as does this one (more Luxuria than Terra) from 1425.

Rabanus Maurus: De rerum naturis. Vatican, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana,

Pal. lat. 291, detail of folio 142r. .

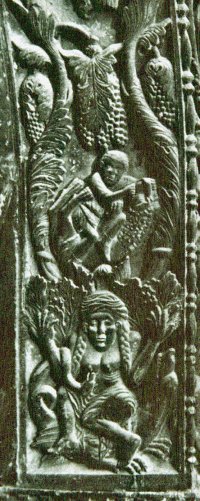

Another rare Romanesque example is on the central portal of the seminal,

Byzantine-inspired Basilica of San Marco in Venice,

where a braided Terra sits amongst stylised palm-fronds, suckling a snake.

At Riom-ès-Montagnes (Cantal) the snake entwines rather than suckles

her on a twelfth-century capital,

but the sheaf of wheat is very obvious. She holds it together with an enigmatic

unsexed but probably male figure.

Her cornucopia seems to feature apples (more appropriate in Auvergne) rather

than grapes.

At Maria-Laach abbey in Belgium, the tails of the snakes are cornucopias.

photo by Martin M. Miles

'Terra suckles a snake and

a pig at Limburg. In a Mount Athos manuscript she suckles a unicorn.'

For other examples, see

Images

of Lust, pages 67-69.

The enantiodromic reversal of Terra is the Femme aux Serpents, symbolising

Luxuria

who is depicted suckling snakes

and other unclean beasts.

Later in the mediæval period appear caricatures, such as this one of

a nun suckling a monkey –

a tiny footnote in a manuscript of the Lancelot Romance at the John

Rylands Library, Manchester.

But there is another strand

to the iconography of snakes:

the Mithraic.

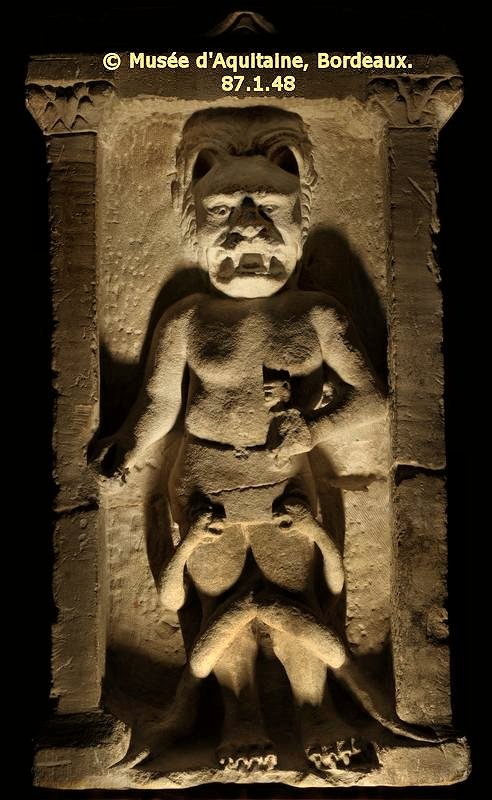

This Mithraic altar from the late Roman period in south-west France depicts

a lion-headed human male-ish figure,

wearing a kind of mini-skirt, with lion-headed serpents entwining its legs.

The serpent represents the journey of the sun (the ecliptic),

and the lion represents the fourth of seven stages of initiation into the

cult.

The key he is holding represents the knowledge which will lead him to the

final stages, opening the doors to wisdom.

Mithras was a deity with loose connections to Mithra and Persian Zoroastrianism,

about whose cult there is good information on Wikipedia.

It was to Romans of the first to fourth centuries rather like Freemasonry

to business and professional men

of the 19th and 20th centuries.

It was an exclusively masculine affair, with members drawn from the middle

ranks of the governing and military (hierarchical) classes.

As with Freemasonry, status within the cult probably assisted status in one's

profession and/or society.

Practised in small, usually subterranean places, including caves, it involved

serious ordeals in stages, of which the fourth

is thought to be the one most commonly reached. The number seven refers to

the planetary bodies: sun, moon and five visible planets.

The central rite of the (chthonic ?) cult was the slaying of a bull representing

the creation of the cosmos.

The serpent represented evil, as in Christianity. But early Christians, who

sometimes shared buildings

with other cults, including Mithraists, managed to suppress the cult quickly

after they gained power

following Constantine's conversion and Theodosius' terrible decree outlawing

all other religions.

This altar illustrates an alternative model for various Romanesque motifs:

scary beast heads, animal-headed humans (theriomorphs), and the femmes/hommes

aux serpents.

It may well have been lit from below in an enclosed space, adding a touch

of terror to its sanctity,

just as gory crucufixions concentrate the mind on Christian mysteries.

A key is also carried by a unique male exhibitionist in Ireland.